The Story

Tis the gift to be simple, tis the gift to be free, tis the gift to come down where we ought to be.

—Simple Gifts, Joseph Brackett, member of the Shaker community in Gorham, Maine, 1848

I was born into an Ordovician landscape of mudstone and shale overlaid with some two feet of rich topsoil, but it was not until I came to know Maine’s untrammeled granite and basalt landscapes that I truly felt at home. As a child, I’d balked at making mud pies, not because I disliked mud, but because making pies seemed a domestic imposition on the raw material of earth. My parents liked to tell that when I was a year old, they found me playing happily with an earthworm, and when they looked again, the earthworm was gone. Presumably I had eaten it. Raw,

Of my ancestors the Strodes, it is written that Strode is Old English for low watery place.

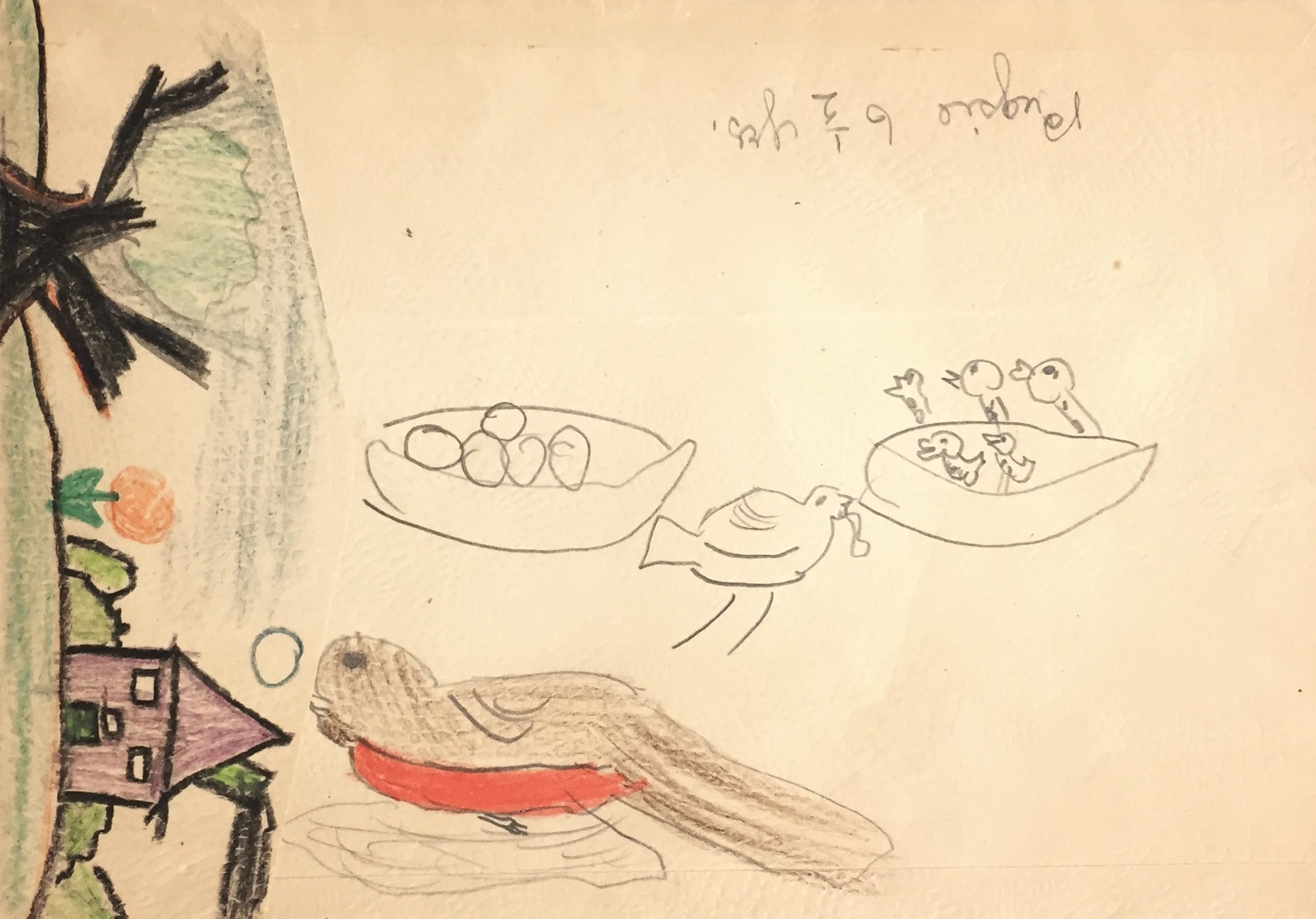

My grandmother on the other side saved many of my earliest drawings. They are of birds, and flowers, and a smiley Jesus. My commitment to habitat restoration and the ways it informs my practice as an artist continue to this day. I listen for the non-human voices that link me to the sacredness of all life.

In fifth grade, our art teacher had us making color splotches on paper, and then outlining them with black. I imagined a wet world populated by salamanders.

In the sixth grade, we made animals. A quartet of bears and an Egyptian cat were my contributions.

“Dudley Zopp first visited Maine . . . at the invitation of ‘Red’ and Peg Garner, her parents’ friends from Lincolnville, and returned once, twice and then three times a year . Her expedition ‘Down East’ to Quoddy Head close by the Canadian border in 1992 was nothing short of an epiphany. Amidst bogs, flora, forests and rocks aplenty, the artist came face to face with the kind of landscape that she had been able to experience previously only in her mind’s eye. There, Dudley found her physical and spiritual center.”

— Bruce Brown, catalog essay, Center for Maine Contemporary Art, 2004

During the eight years I traveled back and forth from Kentucky to Maine, my paintings and installations came to be all about rocks, the way they define Maine’s vistas, the way they hold up the sky, the way they provide a sense of groundedness to the wayfaring traveler. And it was during those years, on solo hikes in Hancock and Washington counties, that I began to experience the landscape as a written phenomenon, a code that could be cracked to reveal the nature of the universe. My experience with yoga taught me that this is none other than the concept of vac, the sound vibrations from which the universe was created and the web that continues to sustain life.

And so I have landed in Lincolnville, Maine, a low watery place, where the evidence of glacial activity takes the form of outcroppings, flows of silt and gravel, and erratics large and small.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, this area was dairy farms where trees were felled, land cleared for agriculture, rocks moved aside to make walls that marked the borders of fields, Now, the resulting open areas invite invasive species such as multiflora rose and barberry, but with work, can be restored as meadows that offer habitat.

Here in the watershed of Bald Rock Mountain, my work includes reshaping the terrain to manage the flow of water; restoring the land to health by encouraging habitat for insects, birds and mammals; and discouraging those invasive species that threaten to destroy habitat for amphibians, choke out mature trees, and crowd out native forbs.

I’ve made changes. Where the seeps were consistent, there is now a pond. Where there had been a trailer and a duplex, there is a meadow and a birch grove. Far from the road, I built my house and studio. And behind the house, there’s a wetland populated with sensitive fern. Where the land rises beyond that, it’s drier, and a small patch of wild blueberries spreads under and out from a line of bayberry.

After just a few seasons of living in this place, my goal was clear. I would plant very little myself, and simply allow the land to heal.

Every year has meant something different. Even though alders provide food and shelter for birds, including the migratory species, they need to be kept in check lest the meadows disappear.

The flow of water changes yearly, increasing with the stronger rains of climate change, but increasing also because the subdivision on the high side of my property continues to provides slope and surface for water to move in my direction.

The goldenrod and asters that are prime habitat for pollinators also spread rapidly, and have taken over some of the meadows, crowding out the Queen Anne’s Lace and buttercups. Through selective mowing, I can encourage these latter species to come back.

I'm in awe of the things that nature provides, from the purple fringe orchid that shows up in the boggy area down by the pond, to the accidental rain garden that's planted itself outside the studio. Even the cattails in the pond are rich in gifts for people and wildlife.

So my art is created as an act of reciprocity. I'm grateful to be able to restore balance to my habitat here in Lincolnville, and my paintings, installations, and books are ways of expressing that.

Biodiversity is a parallel but unrecognized challenge to climate change. No diversity, no food. It’s as simple as that. I intend for my habitat work and my art, these parallel and interwoven practices, to remain equal to each other, to be visible, to raise awareness among a wide range of readers, viewers, and visitors.

“This is the great burden that now rests upon writers, artists, filmmakers, and everyone else who is involved in the telling of stories: to us falls the task of imaginatively restoring agency and voice to non-humans. As with all the most important artistic endeavors in human history, this is a task at once aesthetic and practical — and because of the magnitude of the crisis that besets the planet, it is now freighted with the most pressing moral urgency.”

—Amitav Ghosh, The Nutmeg’s Curse, excerpted in Orion Autumn 2021